Blog 7: Reading

Sequential Art as a

Higher-Order Problem Solving

Skill,

Part 2: Context

Kunst gibt nicht das Sichtbare wieder, sondern macht

sichtbar.

(Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes

visible.)

—Paul Klee, Schöpferische

Konfession (Creative Credo), 1920

Special

Note: The panel I am using for this blog is from Feynman (2011) by Jim Ottaviani, Leland Myrick, and Hilary

Sycamore.

Artists are interpreters

of what they see or imagine. Even photorealism is an interpretation of a subjective

reality based on the eye of the observer (and the talent of the artist). But

what the eye can see also has physical limitations. For example, no one can see

ultra-violet light, so there are no visual representations of it (although I’m

sure someone will figure out a way to bamboozle the public into believing they

have done it, and make a small fortune in the process). Yet most artistic

limitations are not based on universal physics, but rather personal aesthetics.

Artists, like everyone else, edit reality by enhancing what is important, and

deemphasizing (or eliminating) the unimportant—it is how our brains work.

(Zeki, 2005, 100) For sequential artists this happens all the time because the

illustration is in service to the narrative; however, much of the information and/or

details in that narrative must be conveyed visually in order to create meaning.

There is a whole lot more to sequential art than just “talking heads.” So what

does the brain “see” when it “sees” a page or panel of sequential art, and how

does it derive meaning from this literate art form?

Gestalt Psychology

In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud describes Closure as “observing the parts, but perceiving the whole.”

(McCloud, 1993, 30) This is a sideways interpretation of Gestalt psychology’s Law of Closure, in which Kurt Koffka

states: “It has been said: The whole is more than the sum of its parts. It is

more correct to say that the whole is something else than the sum of its parts,

because summing up is a meaningless procedure, whereas the whole-part

relationship is meaningful.” (Koffka, 1935, 176) Koffka begins by referencing Aristotle’s

oft-MISquoted quote, which many of

you may have heard as: “The whole is greater

than the sum of its parts.” In actuality, what Aristotle was saying about Unity was that things “have several

parts [in] which the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is

something besides the parts.’” (Metaphysica, 1045a8–10. See Aristotle’s Metaphysics,13. Unity Reconsidered on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website). What both Aristotle and Koffka are

saying is that when we see only part of something (as in single comic panels for

example), there are more complex and dynamic relationships going on in the

brain—more meaning-making occurring—than simply filling in the blanks.

The Law of Closure works in another

way for sequential art. When drawing a circle, for example, it is better to

make the form with a broken line as opposed to a solid one. With a broken line

the brain becomes more interested in the representation, more engaged with the

drawing, since it has to actively complete the form. A broken line adds energy

to a drawing, whether the illustration is as incredibly intricate as a work by

Joseph Clement Coll (1881–1921),

or as beautifully simplified to its vital essence as rendered by Charles Schulz (1922-2000). Within

Gestalt psychology there are other “Laws” that have meaning to creators of

graphic narratives, and artists in general. Among these are the Law of

Continuity, the Law of Similarity, the Law of Proximity, and the Law of

Symmetry. Gestalt psychology is all about perception and organization, and if

you examine these “Laws” you will find corresponding lessons being taught in

any foundational design class.

Cognitive Psychology and

Dual Coding Theory

Cognitive psychology focusses on how

the brain acquires, processes, and stores information. Perception is a huge

component of cognitive psychology, which is an equally huge component of

sequential art. How we see what we see, and derive meaning from images, has as

much to do with enculturation as it does with physiology. We are a long way

from knowing how much of our aesthetic sensibilities are culturally-based and

how much of it is how our brain is wired (and we may never know); however, what

we do know from the study of cognitive psychology is how we can remember

better, make accurate decisions faster, and become better learners. Some of the

areas of research in cognitive psychology include form perception, pattern

recognition, language acquisition, problem solving, and dual coding theory.

Remember when I wrote in Blog #2 that we need to ask questions that help make

this independent art form grow and evolve? Well, this is a good place to begin.

Cognitive psychology focusses on how

the brain acquires, processes, and stores information. Perception is a huge

component of cognitive psychology, which is an equally huge component of

sequential art. How we see what we see, and derive meaning from images, has as

much to do with enculturation as it does with physiology. We are a long way

from knowing how much of our aesthetic sensibilities are culturally-based and

how much of it is how our brain is wired (and we may never know); however, what

we do know from the study of cognitive psychology is how we can remember

better, make accurate decisions faster, and become better learners. Some of the

areas of research in cognitive psychology include form perception, pattern

recognition, language acquisition, problem solving, and dual coding theory.

Remember when I wrote in Blog #2 that we need to ask questions that help make

this independent art form grow and evolve? Well, this is a good place to begin.

Dual

Coding Theory (DCT) was conceived by Allan Urho Paivio (1925–), a professor

of psychology at the University of Western Ontario. The two major components of

DCT are logogens (verbal system units/words) and imagens (non-verbal system

units/pictures). In DCT, meaning is derived from the relationship between these

two components. Can you say, “Sequential Art?” Not surprisingly, in a 2009

article by Alan G. Gross regarding DCT’s verbal-visual interaction, the author

used a page from Eisner’s Comics and

Sequential Art to illustrate this theory. (Gross, 154) Curiously, Paivio’s Mental Representations: A Dual Coding

Approach (1986), which details DCT was published a year after Comics and Sequential Art. Not that Paivio or Eisner ever met, but it

is fascinating that their two interrelated/interwoven/interlocking theories

appeared in the arts and psychology at the same time (What was in the water

back then?).

There are two types of “Codes” in

DCT: Analogue Codes and Symbolic Codes. Analogue Codes refer to images in our

minds based on what see, or have seen, in the real world. Symbolic Codes are those

things, such as writing, or icons, that represent a concept or idea. Symbolic

Codes are divided into verbal and non-verbal subsystems, which are then divided

into visual, auditory, and/or haptic sensorimotor subsystems. (Paivio, 1986,

54) McCloud covers Symbolic Codes in depth in Understanding Comics when he writes about “Icons.” (McCloud, 1993,

24-59) For graphic eTextbook creators, having a working knowledge of cognitive

psychology, especially DCT, would be a plus.

Neuroscience

“Visual artists are, in a sense, neurobiologists

of vision, studying the potential and capacity of the visual brain with

techniques that are unique to them.” (Zeki, 2002, 918) How does the brain

process art? Inner Vision: An Exploration

of Art and the Brain (1999) by Semir Zeki, professor of neuroesthetics (his

term) at University College London lays some interesting groundwork into

understanding how art works. Currently, neurobiologists know more about how the

brain responds to color, motion, and depth systems than they do about form

systems, but that is quickly changing with strides in computational

neuroscience’s understanding of neural networks. However, there is a small area of

Zeki’s neuroaesthetics that I want to briefly discuss.

“Visual artists are, in a sense, neurobiologists

of vision, studying the potential and capacity of the visual brain with

techniques that are unique to them.” (Zeki, 2002, 918) How does the brain

process art? Inner Vision: An Exploration

of Art and the Brain (1999) by Semir Zeki, professor of neuroesthetics (his

term) at University College London lays some interesting groundwork into

understanding how art works. Currently, neurobiologists know more about how the

brain responds to color, motion, and depth systems than they do about form

systems, but that is quickly changing with strides in computational

neuroscience’s understanding of neural networks. However, there is a small area of

Zeki’s neuroaesthetics that I want to briefly discuss. It should be no surprise that

different areas of the brain are functionally specialized. Some areas process visuals,

such as motion, color, form and faces, while others process information from

the other four senses. Yet even cells are specialized. There are, for example,

orientation-selective cells, “which respond selectively to straight lines and

are widely thought to be the ‘building blocks’ of form perception.” (Zeki,

2005, 99) According to Zeki, this is why artists such as Piet Mondrian (1872–1944)

began experimenting with line and non-figurative art. Mondrian believed that

there was a configuration made up of lines, squares, and rectangles that was serene, or “free of tension.” (Zeki,

1999, 123) What neuroaesthetics is discovering now is that this “plurality of

straight lines” is “admirably suited to stimulate cells in the visual cortex.”

(Zeki, 1999, 124) With that in “mind,” I wonder how much the panel

“grid” of the sequential art page plays a part in preparing the brain to

receive information?

It should be no surprise that

different areas of the brain are functionally specialized. Some areas process visuals,

such as motion, color, form and faces, while others process information from

the other four senses. Yet even cells are specialized. There are, for example,

orientation-selective cells, “which respond selectively to straight lines and

are widely thought to be the ‘building blocks’ of form perception.” (Zeki,

2005, 99) According to Zeki, this is why artists such as Piet Mondrian (1872–1944)

began experimenting with line and non-figurative art. Mondrian believed that

there was a configuration made up of lines, squares, and rectangles that was serene, or “free of tension.” (Zeki,

1999, 123) What neuroaesthetics is discovering now is that this “plurality of

straight lines” is “admirably suited to stimulate cells in the visual cortex.”

(Zeki, 1999, 124) With that in “mind,” I wonder how much the panel

“grid” of the sequential art page plays a part in preparing the brain to

receive information?

Putting it All Together

So, how does the brain process

information from a graphic narrative? While we see whole pages of art we do not

read whole pages of art—we read panels. Panels are the “building blocks” of

sequential narratives, and, as we migrate to digital platforms with smaller and

smaller screens, I believe the medium will need to focus less on traditional page

design and more on screen/panel design (more on that in Blog #9). Here is what

I believe is happening when the brain interprets a panel of sequential art, and

tries to derive meaning from it. Understand that the idea of the brain being wholly

right or left is very simplistic, but it sells a lot of mass-market books. The

brain is much more complex than that, and information readily passes back-and-forth

between the two hemispheres. Yet for all that complexity, the process of

reading graphic narratives is deceptively

simple, which is why, I believe, they get such short shrift. The first

example below is “basically” how the brain “sees” a panel of art.

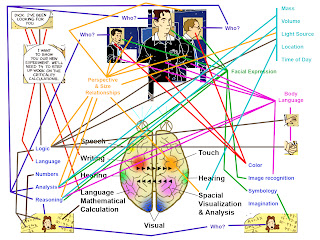

The second panel below is what happens when the brain disassembles (my term) a panel, and tries to decipher it, and derive meaning from it. Remembering that the brain is not modularized, but highly complex and interconnected (language is in multiple areas for example), here is a simplified visual to help describe what is happening in lay terms. Who are the individuals in the panel? How do they relate to one another? How do they exist within their space? What does the text say? Does the text match the facial expression and/or body language of the speaker, or is there some sort of subtext being conveyed? Does color have meaning? There are thousands of questions just like these being asked in the time it takes to “read” the panel before going on to the next one, but there is still more to it than that. When the brain is engaged in “reading” a graphic narrative it comes to a panel, disassembles it, analyzes it for content, reassembles it, places the panel’s narrative (both verbal and non-verbal) in context with every panel that has come before it, draws conclusions as to the information’s place in the ongoing narrative, and then moves on to the next panel where the process begins again—all in the space of a few seconds.

There are many more elements at work

in this whole-part dynamic relationship of graphic narratives, Horatio, than

are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Topics for Discussion

1)

What other areas of philosophy, psychology, or neuroscience are missing from

this discussion?

2)

How do we go about testing how the brain actually receives information from

graphic narratives?

Next Blog: Designing Graphic

eTextbooks, Part 1: Developing the Narratives

I find this explanation of how our brains process sequential art very insightful.

ReplyDelete